Options are often difficult to understand, but read this article, and I can almost guarantee you’ll be a lot more knowledgeable about how they work.

We’ll begin with a boring practical real-world example followed by a silly analogy which will burn it into your memory permanently!

What is a call option?

A call option is a contract that you enter with the option seller. Buying a call option gives you the right to buy a stock, say, Shopify (SHOP), for a price you choose (the strike price) within a certain number of days.

Remember: all options expire after a certain number of days. Options with expiration dates that are further away are more expensive because of the time value of money and the increased risk to the option seller that the stock price will go up and hit the strike price.

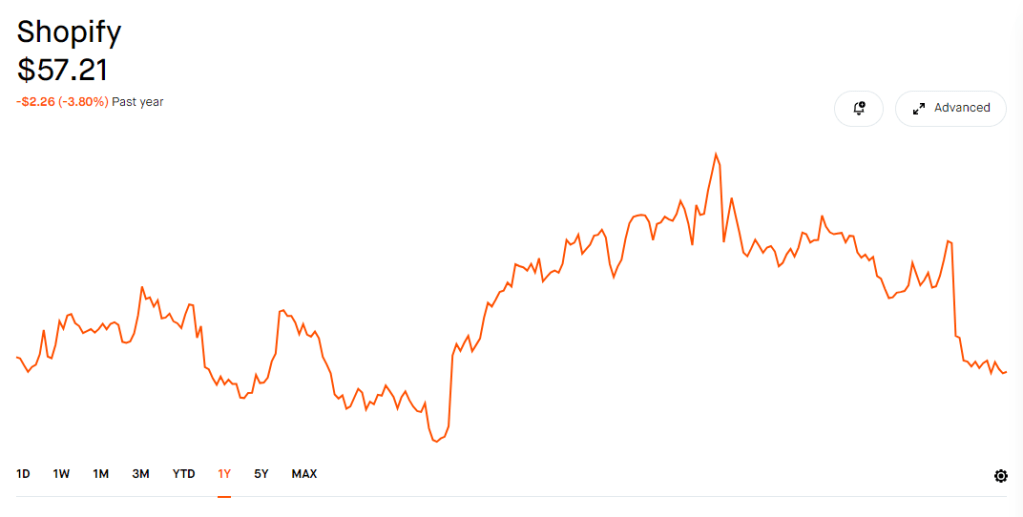

Let’s say you think Shopify has bottomed out and you want the right to buy 100 shares of the stock for the next 30 days.

As you can see by the chart, it dipped quite a bit post-earnings, but appears to be hitting some resistance!

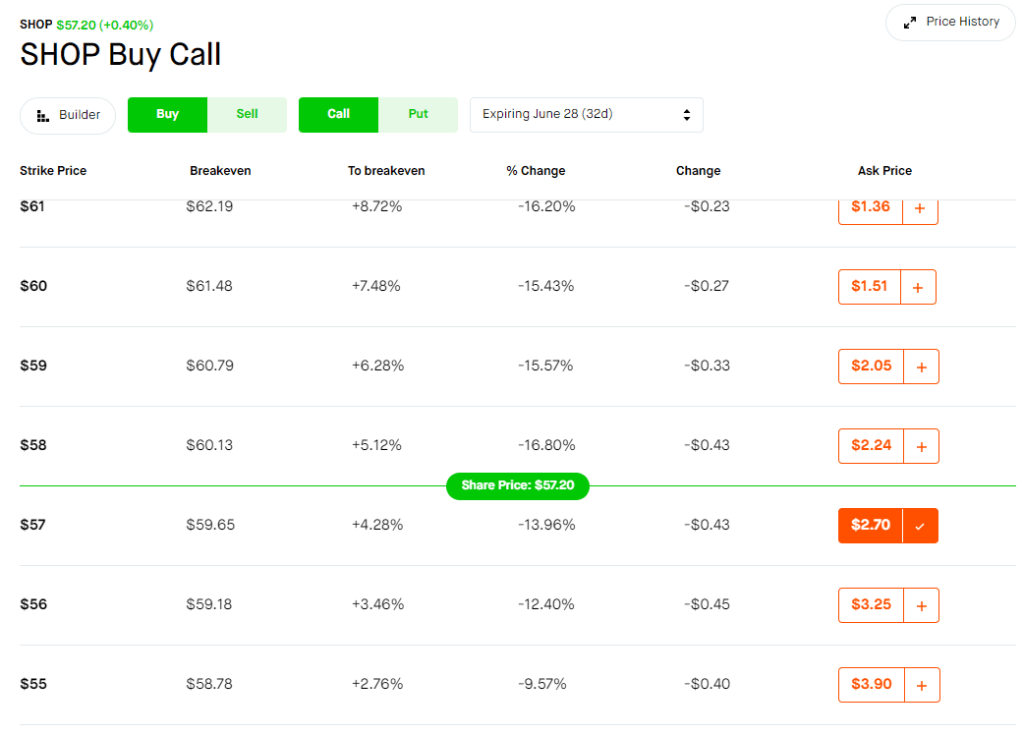

So, you go to the option chain and buy a call option with the following parameters:

- Strike price: $57

- Price paid to enter the option contract (Premium): $270 (or, $2.70 per share)

- Expiry date: June 28 (32 days from now)

The stock is currently trading at $57.20, but you need it to increase a bit more so that it becomes worth it to exercise your option. You need the stock to surpass your “breakeven point.”

Your break even price is calculated as follows:

$57.00 + $2.70 = $59.70

That means, if Shopify’s stock price rises above $59.70 per share, it would become worth it to exercise the option for your right to buy 100 shares at $57/share.

For example, if the price rose to $65, and you exercised your option, your all-in cost per share would be the $57 per share you paid to buy the stock, plus the $270 you paid to enter the option contract.’

Your total cost would be calculated as follows:

$5700 + $270 = $5,970

Or: $59.70 break-even price x 100 shares = $5,970

You could the turn around and sell the shares for the prevailing market rate of $65 per share and make a profit.

Your profit would be calculated as follows:

$6500 (100 shares at $65 per share) – $5,970 (your all in cost) = $530 (your profit)

Remember, if the stock doesn’t rise above the break-even price, the $270 call option you bought expires worthless.

Understanding call options through a silly analogy

Pretend you’re a bazillionnaire.

After a night of heavy drinking, you decide you want to buy Jeff Bezos’s super-mega yacht. Unfortunately, Jeff has another potential buyer: Dua Lipa.

Before you buy it, you want to check with your accountant to make sure buying a super-mega yacht is a good investment. In order to buy yourself some time to do this, you offer to pay Jeff $50,000 today in exchange for the right to buy the super-mega yacht within the next 14 days for the low-low price of $100,000,000.

The next day, you wake up feeling sober enough to talk to your accountant, who persuades you that buying a super-mega yacht is not a fiscally prudent move. You grudgingly agree.

After 14 days of ignoring Jeff, who had since been blowing up your phone (no doubt inquiring over your interest in buying the yacht), you allow the option to buy the yacht to expire.

This means that Jeff’s obligation to keep the super-mega yacht available for you in case you wanted it has lapsed and he is now free to turn around to sell it to Dua Lipa or to whoever else wants it.

Unfortunately, this means he gets to keep the $50,000 you gave him for the option to buy it, since the time constraint in the contract has been met. Using option-trader lingo: the option you bought expired worthless.

Fortunately for you, you’re better off wasting $50,000 than $100,000,000 on a super-mega yacht. Perhaps the rubber dingy collecting dust in your garage is really all you needed to have a good time after all. Besides, you know what they say about the word boat: it stands for “Bust out another thou!”

Awesome story, but what does it have to do with options?

The data points in the above example are analogous to the three main components of an option:

- $50,000: is analogous to the option premium you pay to buy a call option

- $100,000,000: is analogous to the strike price – the price you lock in and at which you can buy 100 shares of the underlying stock

- 14 days: is analogous to the expiry date of the option. Remember: all options expire!

If you can understand this example, you’ve got the concept down.